THE HOPWOOD FILES

For more than 50 years Bert Hopwood was a key player in British bike design. CB gets exclusive access to his documents, letters – and previously secret designs

Words: MICK DUCKWORTH Photography: NATIONAL MOTORCYCLE MUSEUM, HOPWOOD ARCHIVES, BAUER

Bert Hopwood had a major role in engineering BSA, Norton and Triumph’s most successful classics. So when CB got the chance to see some of his formerly strictly confidential designs and documents, we couldn’t resist.

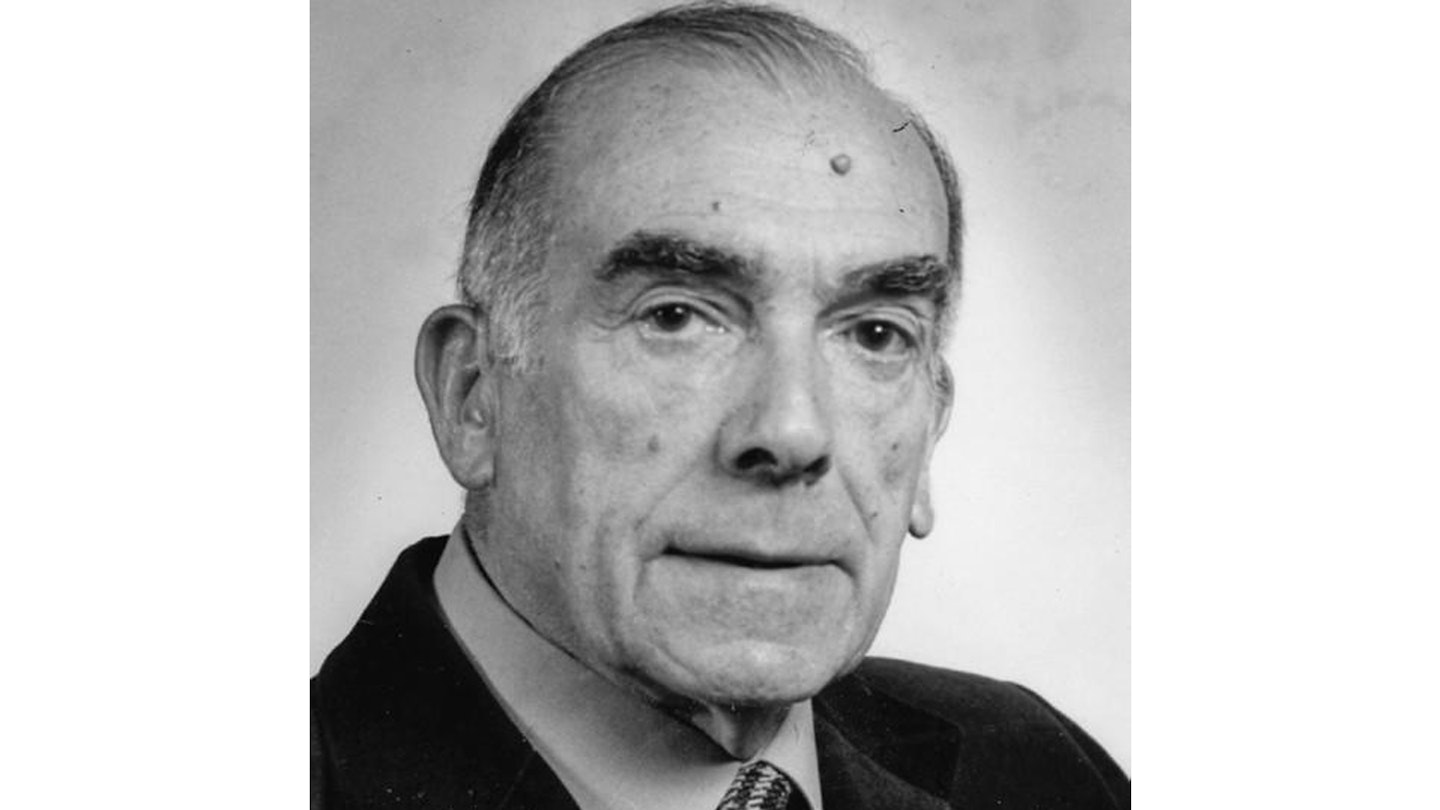

Hopwood’s career started as a draughtsman at Ariel in 1926, assisting chief designer Edward Turner and following him to Triumph in 1936. He joined Norton as chief designer in 1947, but was sacked two years later and moved to BSA as chief engineer.

He resigned in 1956 to rejoin Norton as a director, until being invited back to Triumph (owned by BSA since 1951) by Turner in 1961. When Hopwood died in 1997, he left a cache of documents, brochures, photos and engineering drawings in his Torquay home, which a relative retrieved. On that relative’s death, his friend Nick Hoad acquired the collection. Last year, he donated the archive to the National Motorcycle Museum, whose director James Hewing gave CB access.

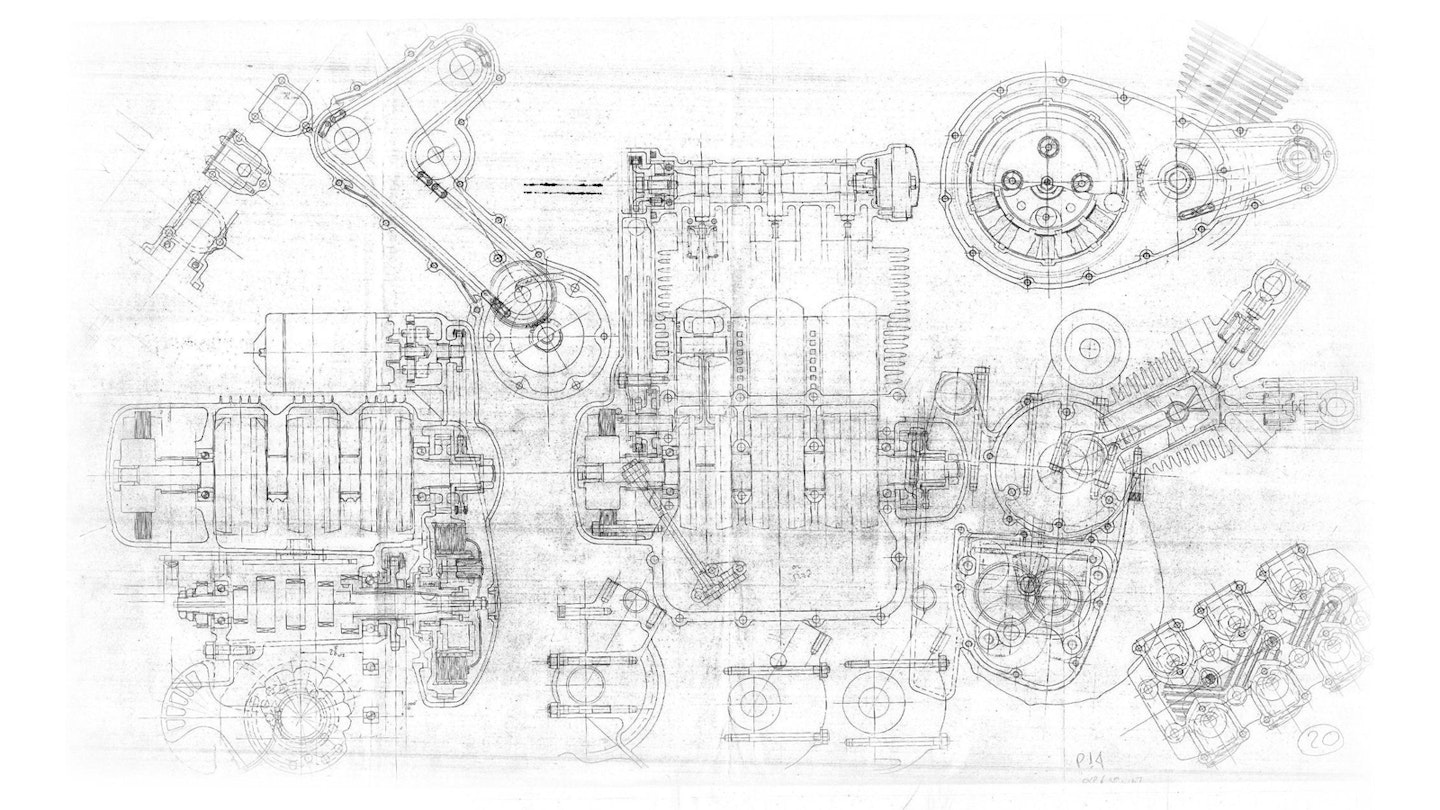

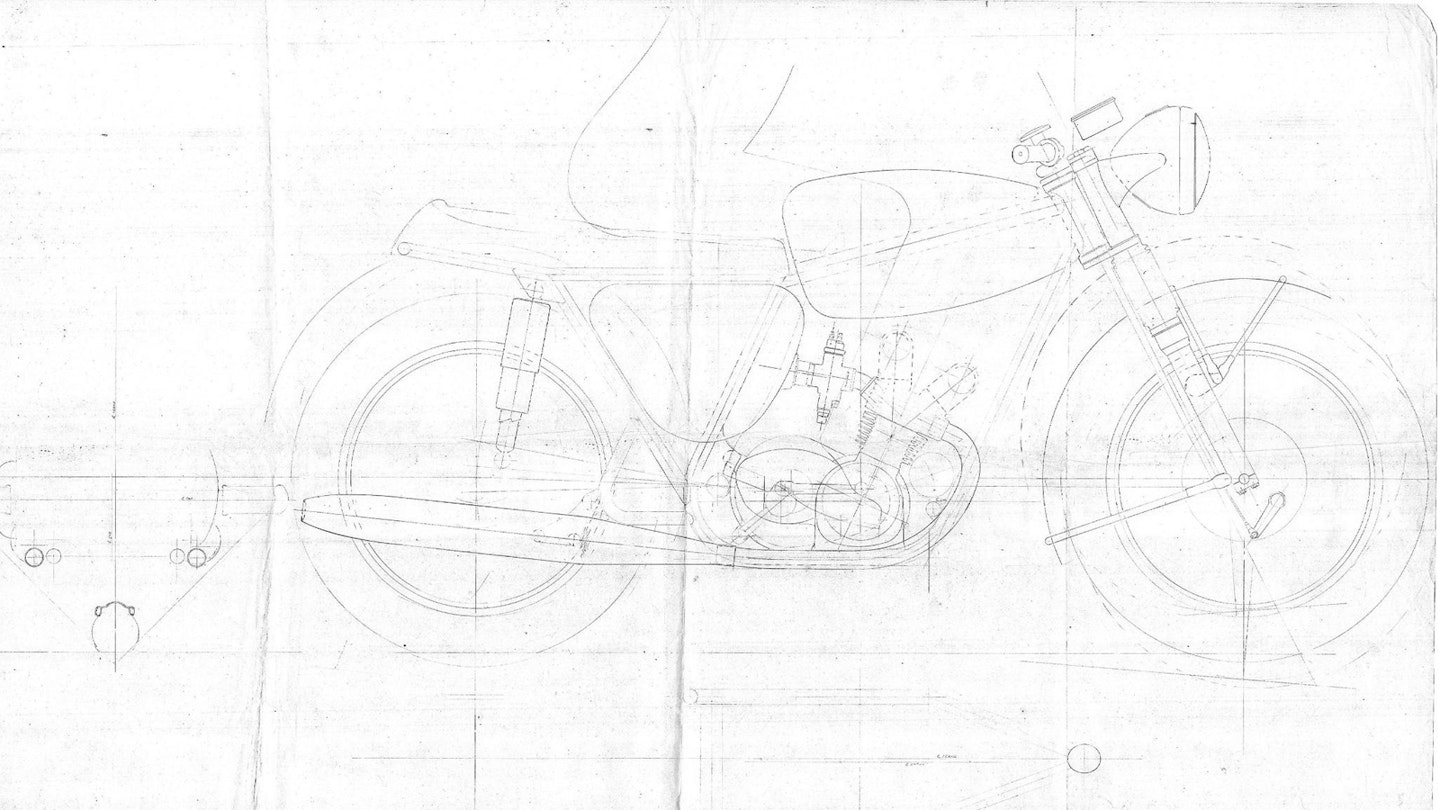

Most of the drawings were produced when Hopwood was chief engineer at Triumph. Three particular plans highlight a family of high-performance dohc engines that never reached production. Dating from 1967, they show proposals for a 125cc single, a 350 triple and a 500 four. According to Hopwood’s book Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry? (published in 1981) he agreed with managing director Harry Sturgeon on the need for ‘modular’ designs to rationalise production across the BSA and Triumph ranges.

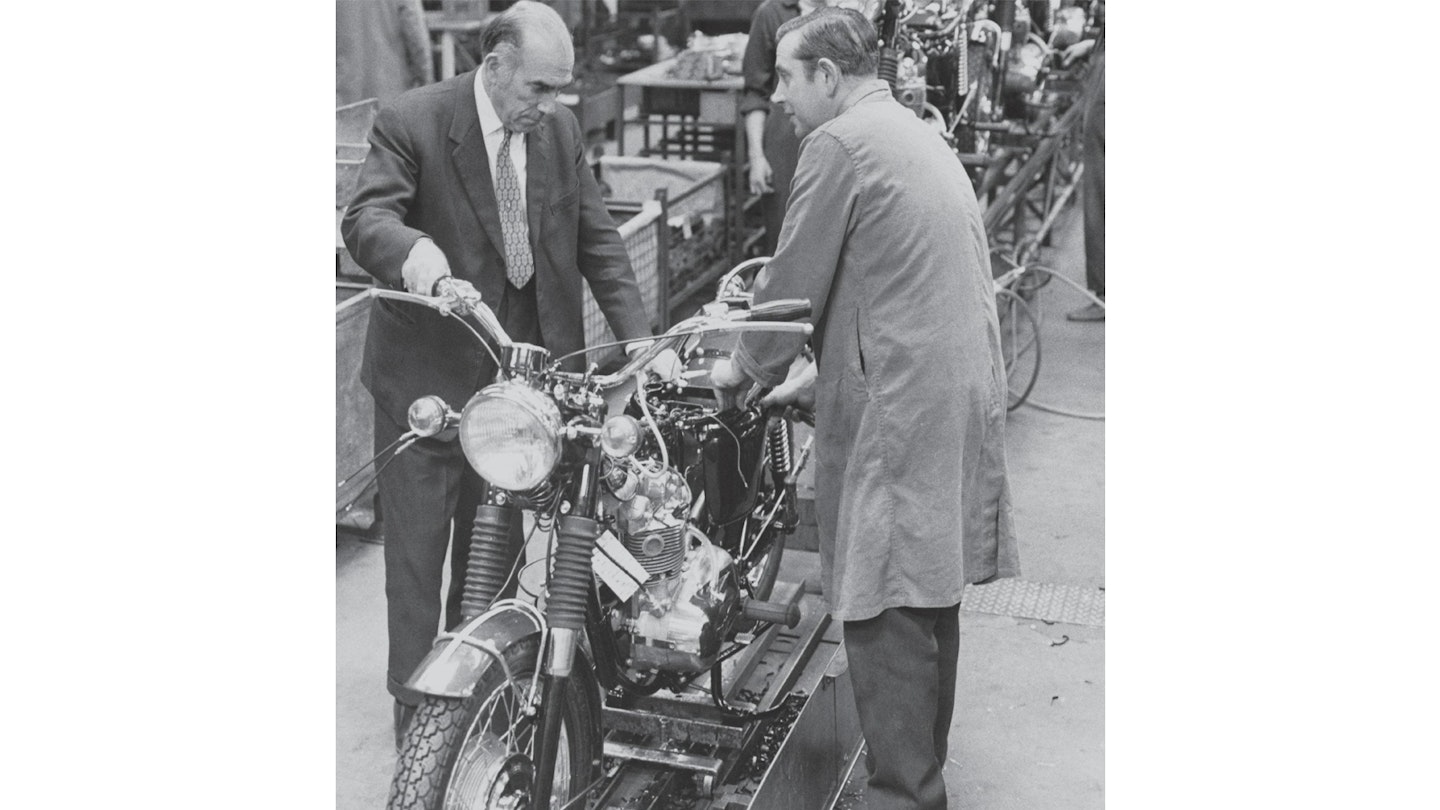

Why didn’t these radical designs get off the drawing board? In 1967, the company had other priorities. Triples supporter Sturgeon died from a brain tumour and the less-focused Lionel Jofeh came in as MD. Triumph’s Meriden factory was at full-speed producing big twins to meet US demand, while BSA’s Small Heath plant was gearing up to make 750cc three-cylinder engines – first proposed by Hopwood in 1963 – for the BSA Rocket 3 and Triumph Trident’s launch in mid-1968.

Although work did not proceed on these designs, Hopwood and his right-hand man Doug Hele held on to their vision for modular products ranging from a 200cc single through twins, triples and fours of escalating size up to a 1250cc V5 flagship. They persevered with the project until offering it to incoming Norton Villiers Triumph rescue management in 1973… when it was brushed aside as too ambitious.

The following gives an in-depth look at the secret-until-now engines, plus insight into what it was like behind the BSA-Triumph factory doors during Hopwood’s time thanks to previously confidential letters and documents.

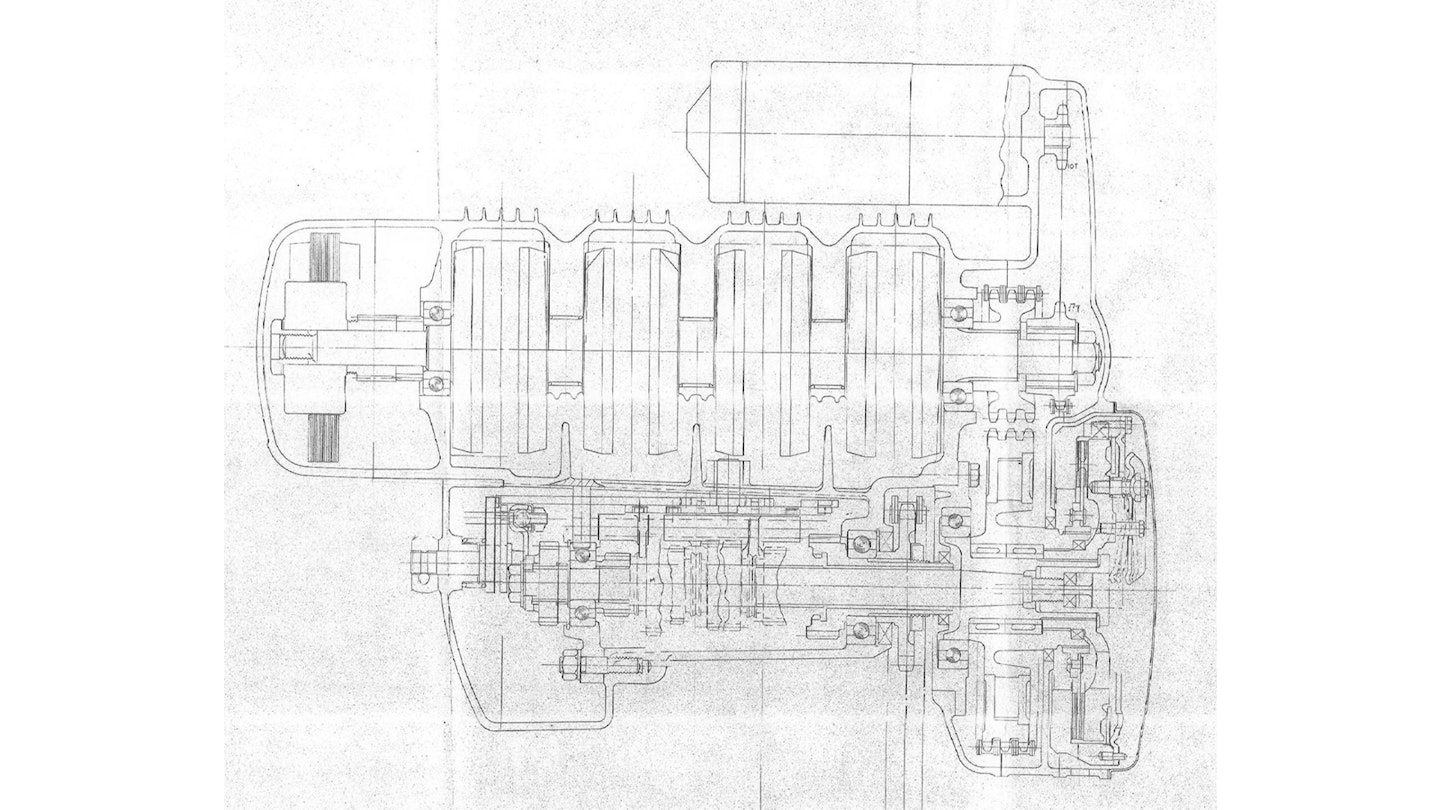

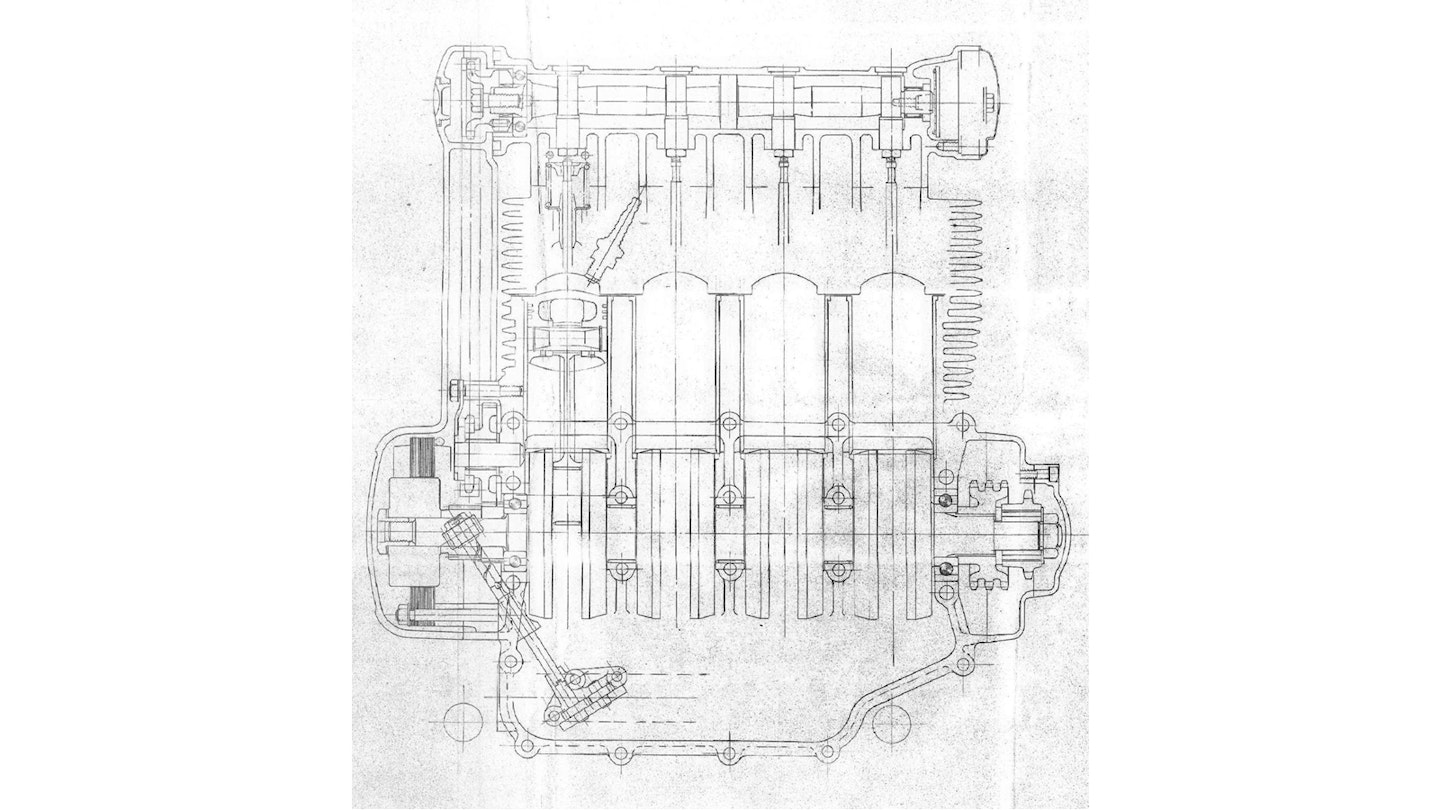

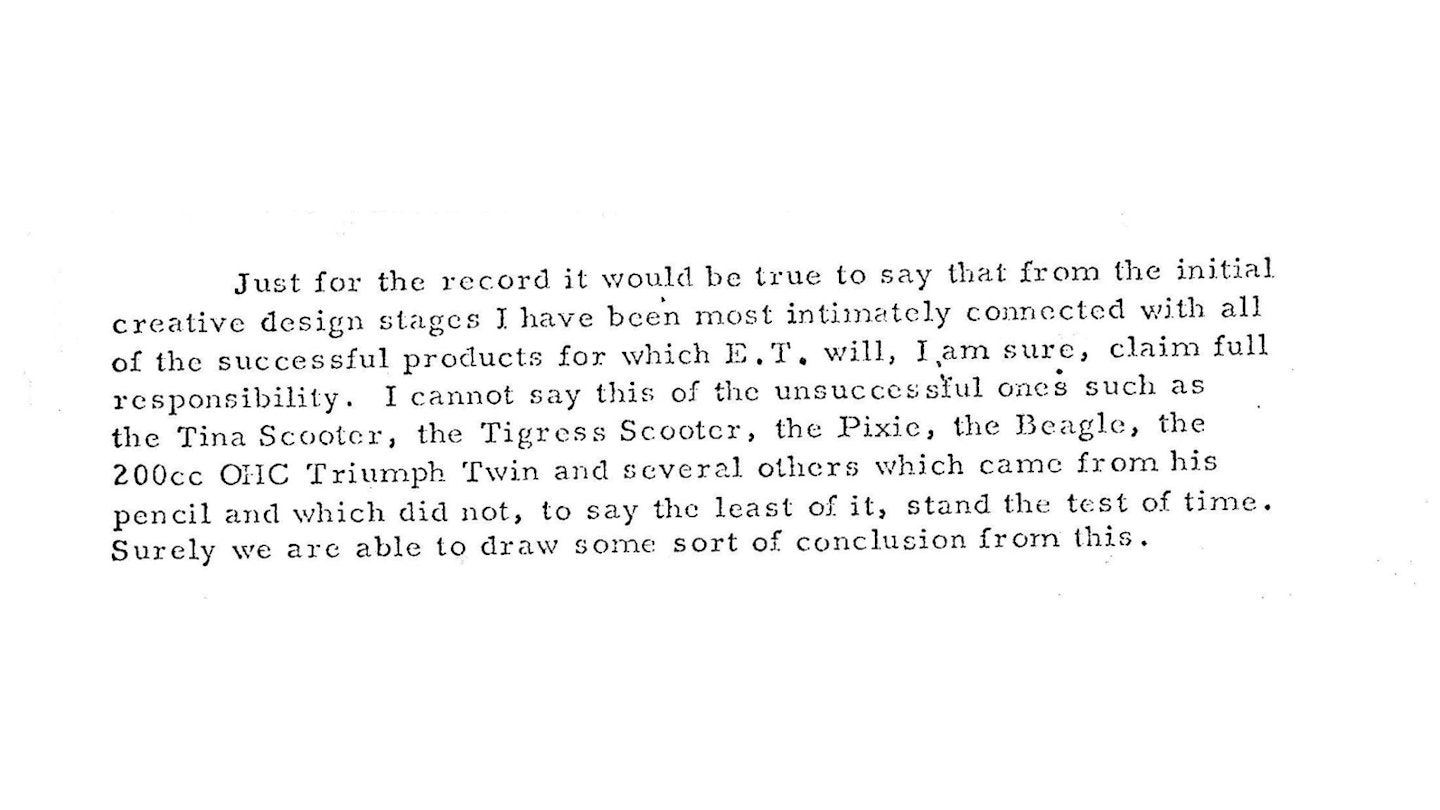

500cc DOHC INLINE FOUR

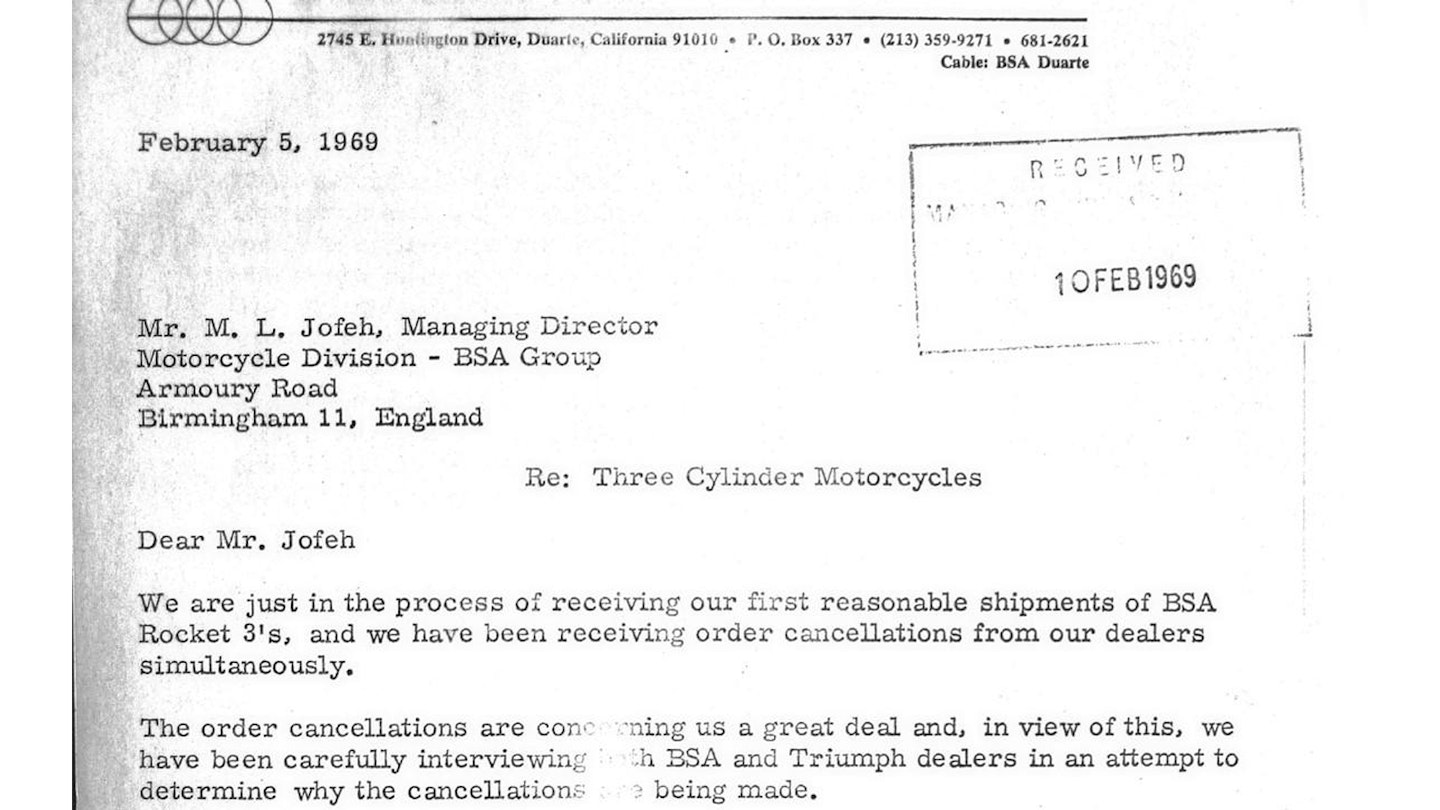

Pete Colman, boss of BSA Western in California, sent a letter to Triumph MD Lional Jofeh in February 1969 (right). It carried bad news about sales of the firm’s new 750cc triples. Dealers were cancelling orders for the BSA Rocket 3, some believing it’d be impossible to sell against Honda’s four-cylinder CB750 which was due that summer – and likely to cost less. Silencer and fuel tank shapes and colours were disliked, and oil leaks criticised.

Hopwood’s response, kept in the archive with the letter, points out that a 750cc triple could have been produced in 1965. And even more interestingly, Triumph could have been ahead of the game with their own four-cylinder machine had this design from 1967 been pursued.

The biggest engine of Bert’s three dohc designs, it has bore and stroke dimensions of 54 x 50mm to give a 458cc short-stroke inline four with cylinders inclined forward at 30°. It is not clear whether the one-piece crankshaft’s big-end journals are disposed at 90 or 180°. Five main bearings consist in a ball-race at each end, with three plain shells supporting the inner section.

The crankcase is split vertically and laterally through the bearing centres, with insert plates supporting the inner mains. The connecting rods’ cap joints are angled at 45°, allowing nuts on the big-end bolts to be easily accessed during assembly or servicing. Piston crowns are shaped to create squish, and equally-sized inlet and exhaust valves are set at an included angle of 65° – narrower than traditional British engines.

These features bear the mark of Doug Hele, a less conservative engineer than Hopwood. Combined with twin overhead camshafts and a short stroke, they indicate a design aiming for high revs and strong performance, with 65bhp or more in view – more than the standard 740cc Trident and Rocket 3 triples.

‘Twin camshafts and a short stroke, with 65bhp or more in view – more than the 740cc Trident’

A wet sump with a nose at the front containing an oil filter houses a gear-type oil pump. A straight-cut gear inboard of the pump drive meshes with a combined half-time gear and sprocket to drive the camshafts by chain. Each camshaft runs in four plain bearings, the lobes opening the valves by depressing sliding pushers, with threaded tappet adjusters. While less easy to adjust, bucket-and-shim tappets commonly used in dohc engines by the 1960s would have been more compact.

Primary drive to the five-speed gearbox is by triplex chain – via a single-plate clutch, as on 750cc triples – with ballraces supporting the mainshaft on either side of the output sprocket.

A Lucas alternator is positioned outboard of the camshaft drive, while at the other end of the crankshaft the drive from an electric starter in front of the crankcase is by chain.

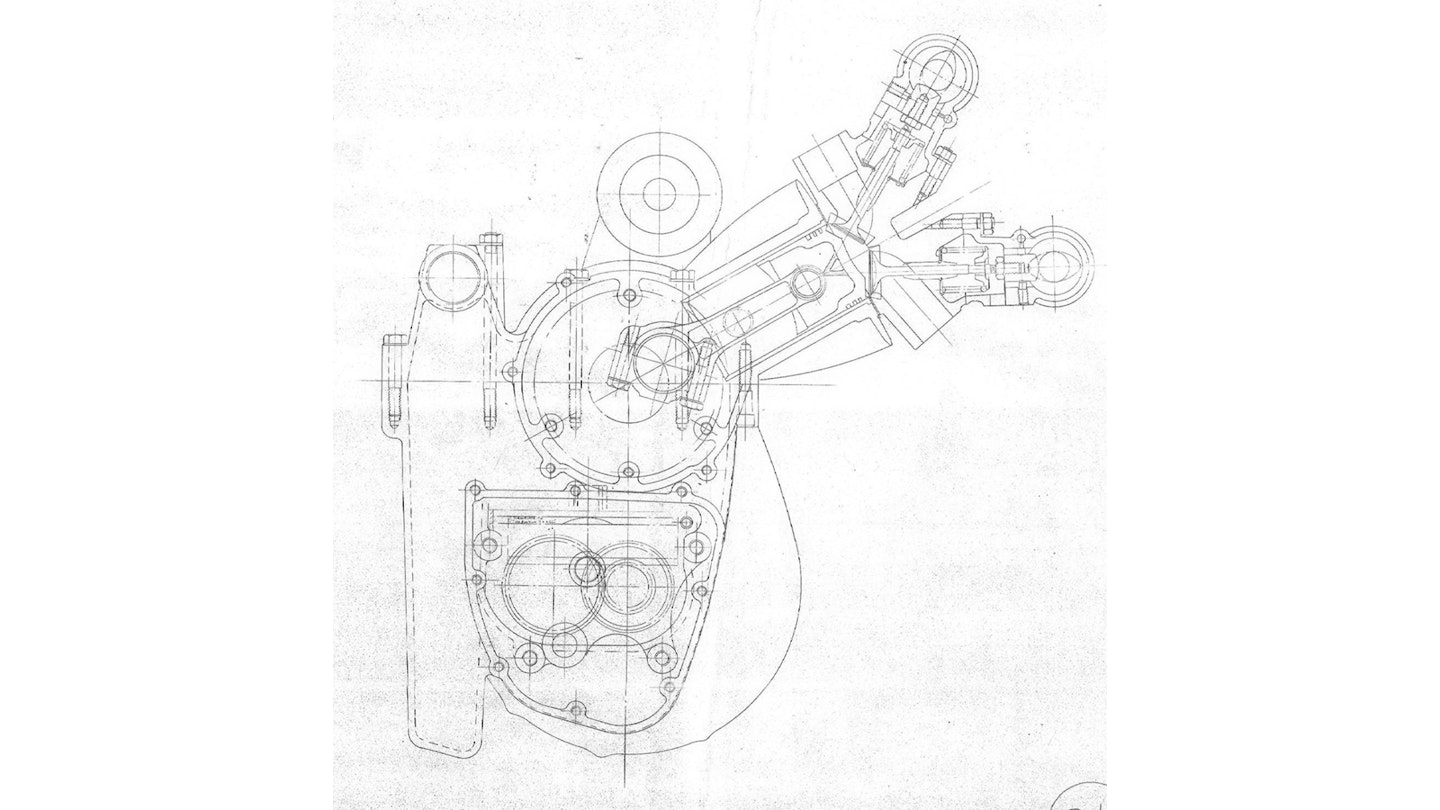

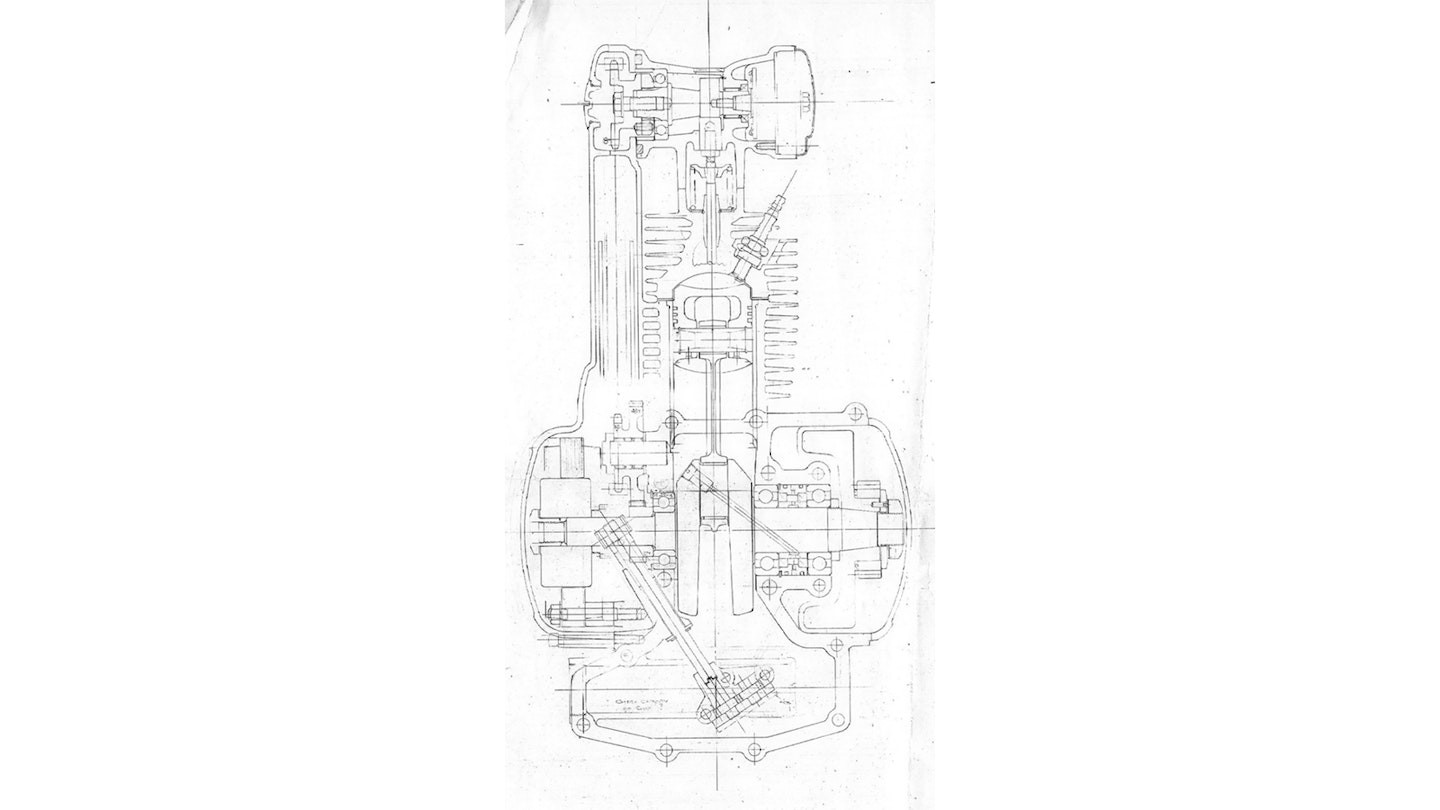

350cc DOHC TRIPLE

There were some massive rows during Hopwood and Edward Turner’s decades-long relationship. In his book, Bert said he admired ‘ET’ for his inventive genius and flair for design, but thought his grasp of engineering and mathematics was poor. Saved letters evidence acrimony over the development of a 350cc machine needed to counter Japanese products in the US entry-level market.

In a report from a 1966 US visit, BSA chairman Eric Turner (no relation to Edward) suggests a 350cc triple that Hopwood and Doug Hele had on the drawing board would sell well – and envisaged producing up to 50,000 of the bikes per year. Seeing the design, we’re inclined to agree.

This arrangement shows features common with the 500cc four, the same bore and stroke giving 343cc with three in-line cylinders. The big-end journals are likely at 120°, as in the BSA/Triumph 750 triples. The valve angle is narrower than on the four at 55° and the combustion chamber shape different, but valve actuation is the same as the four (and similar to a 1964 drawing of Hele’s proposed 250cc triple, seen in Norman Hyde’s Winning Ideas book). Primary drive is by gears, direct from the crankshaft to a multiplate clutch. It features a five-speed gearbox.

But Eric Turner changed his mind. Rather than a triple, he and BSA’s MD Lionel Jofeh chose a dohc 350cc parallel twin designed outside the main factories by Edward Turner in retirement.

‘BSA chairman Eric Turner envisaged producing up to 50,000 per year’

This irked Hopwood, especially when he saw a letter ET wrote to Jofeh in October 1968, warning him to keep Hopwood away from the project. Bert wrote to Jofeh, complaining of the ‘insulting statement and innuendo,’ pointing out that he had refused to have anything to do with the ‘ET 350’ because there was ‘so much fundamentally wrong’. It seems that was true – in a letter Jofeh wrote, he declines to pay Turner an advance of royalties, because a prototype engine had broken on test and further work was clearly needed.

In a long programme coded P30, the twin-cylinder engine was extensively redesigned (including the use of an inverted L-shape of the left-side camshaft drive, as on this drawing for the triple) and got a stronger frame in Reynolds Tube commissioned by Hopwood. Despite this, the resulting BSA Fury and Triumph Bandit models were cancelled on the eve of production in 1971.

If this three-cylinder unit had been prototyped and developed instead, it could have produced considerably more power than the Bandit/Fury’s 34bhp.

‘Bert said there was “so much fundamentally wrong” with Turner’s 350’

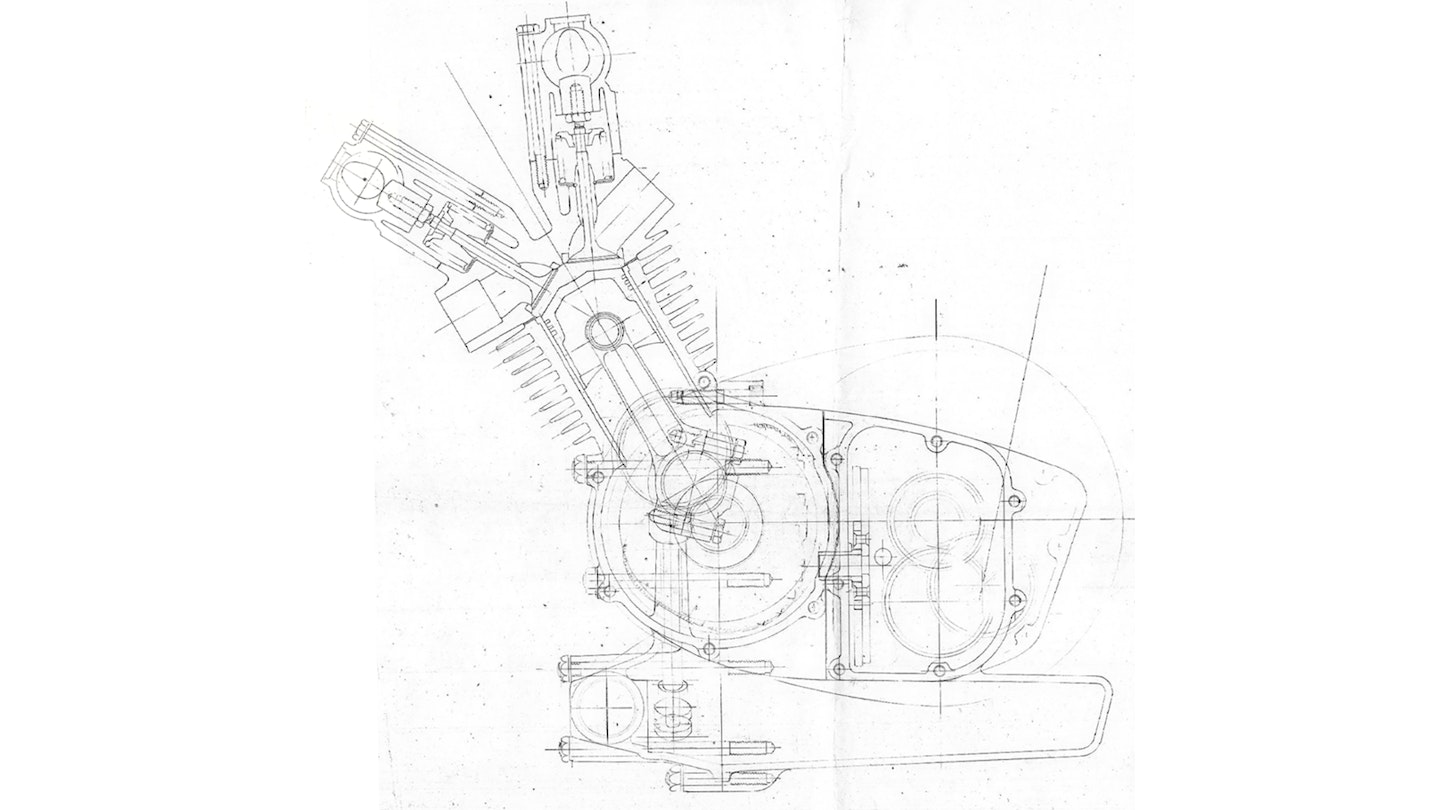

125cc DOHC SINGLE

With a bore and stroke of 54 x 54mm (124cc), this is basically a portion of the triple with the same 55° valve angle and gear primary drive, but with a four-speed gearbox and two-plate clutch.

Its performance potential shows it was intended as more than just a Tiger Cub replacement. No electric starter is deemed necessary and there is a flywheel adjacent to the doubled-up main bearings on the drive side of the crankshaft.

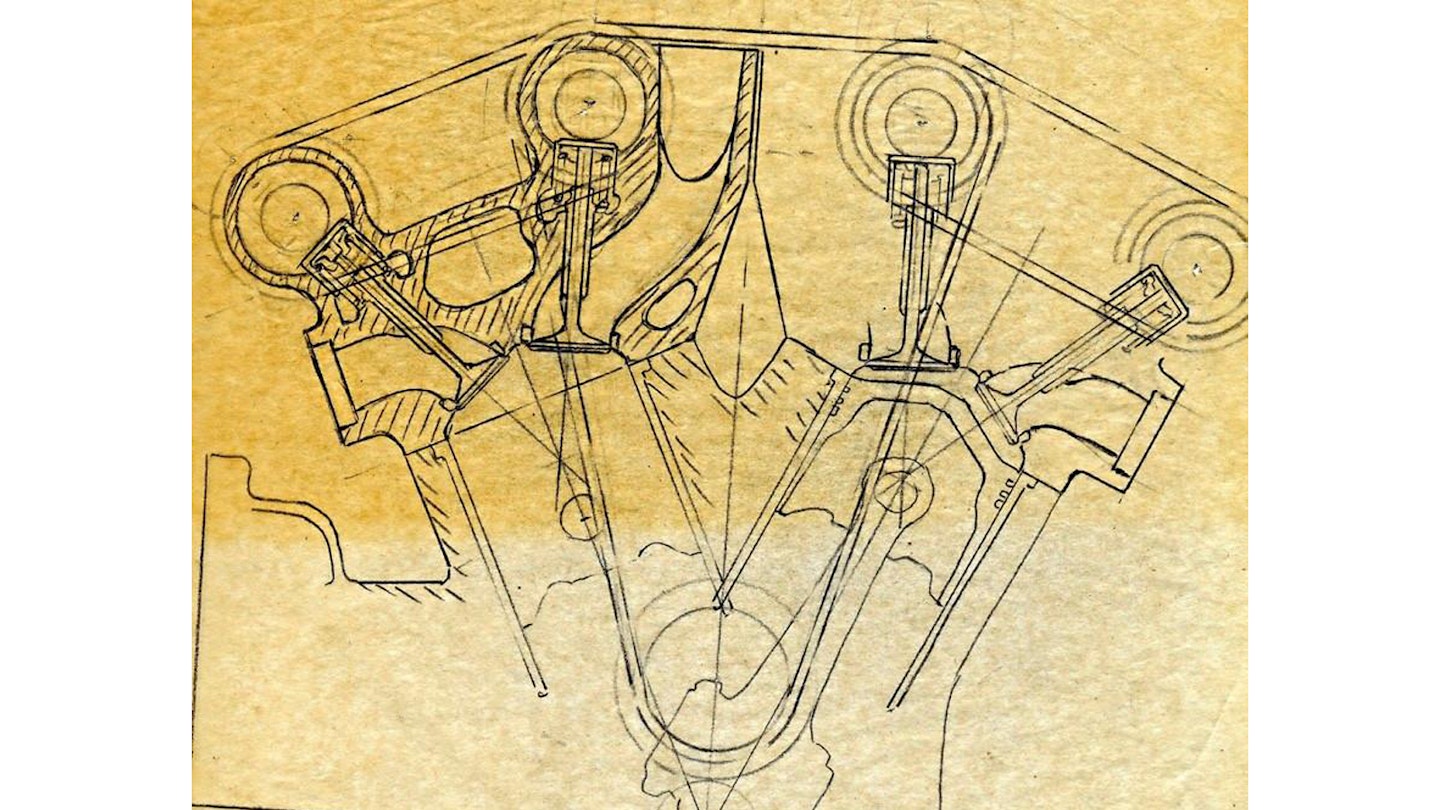

MYSTERY MOTORS

There are other drawings in the intriguing stash other than the modular dohc designs. Among a stack are curious schemes for V-twin engines, probably also from Hopwood’s own pencil. One shows a 50° V-twin with two chain-driven camshafts, while the other has a single camshaft combined with water cooling. Both feature vertical inlet tracts and a deep wet-sump crankcase with output 90° to the crankshaft axis, suggesting shaft drive (or perhaps a non-motorcycle application).

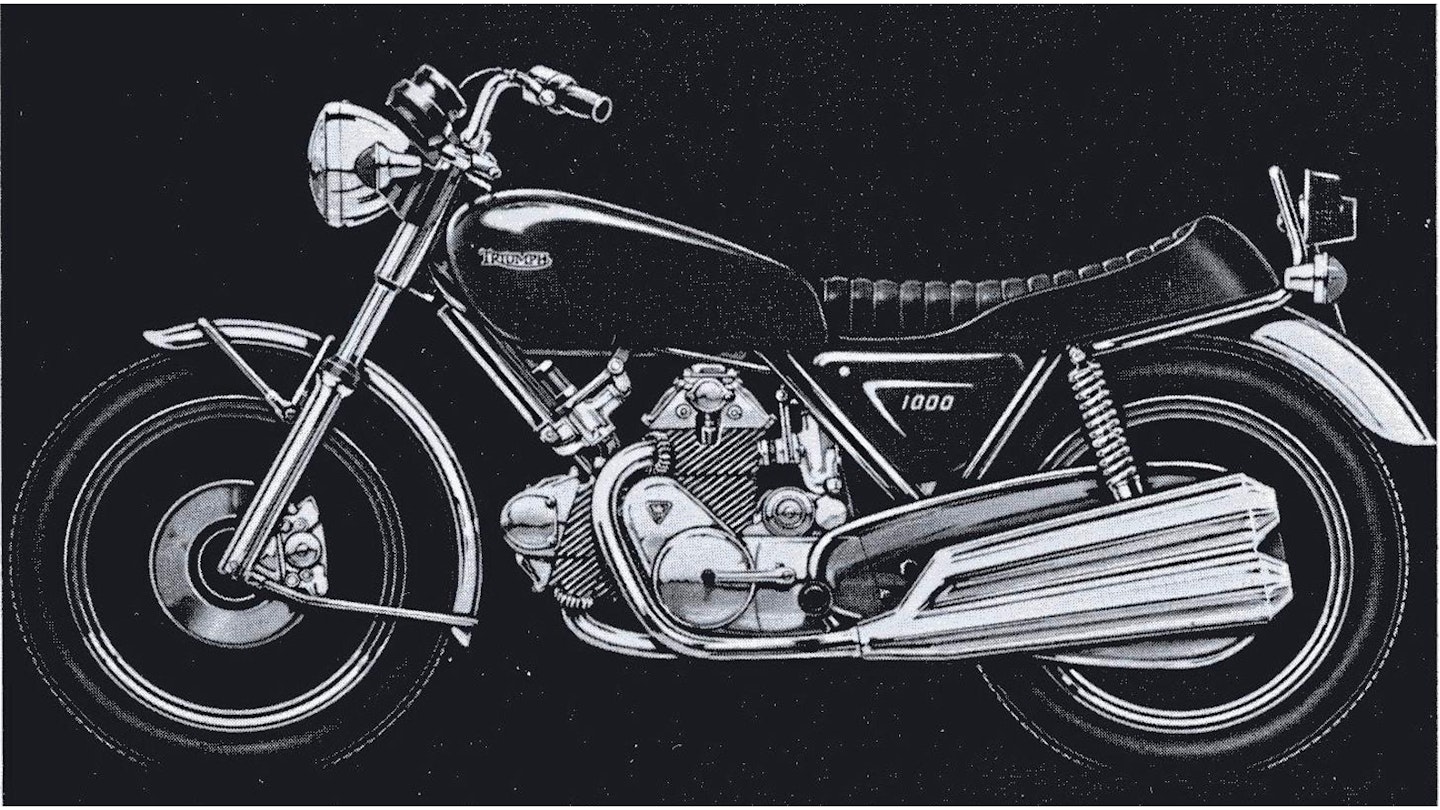

Hopwood’s only known V-configuration designs are the 1000/1250cc V5 versions of his and Hele’s modular range, proposed for the late 1970s.

ENOUGH IS ENOUGH…

When Norton Villiers Triumph took over running Triumph after the collapse of BSA in mid-1973, Hopwood’s plans for a new range of modular machines were ditched. He resigned as technical director at Triumph in August 1973, citing ‘fundamental differences of opinion with the present management’.

Letters show his departure did not go smoothly. Concerned at how it should be made public, NVT Chairman Dennis Poore drafted a press release for Hopwood’s approval – but also suggested an alternative, merely stating Bert had retired (he had turned 65 in August). Poore was concerned that the press would ‘seek more details on the disagreement’.

Hopwood insisted on the ‘fundamental differences’ wording and raised the question of a termination payment on top of his company pension. He also referred to an ex-gratia pension payment promised him by former BSA chairman Eric Turner and wanted to know how much it would cost to buy his company car from the leasing company.

In October 1973, when Meriden workers were occupying the factory in response to discovering it would close, Poore asked Hopwood if he’d had any contact with sit-in leader Leslie Huckfield MP and his plan for a workers’ co-operative. He’d heard from press sources that Hopwood was ‘proposing to make a substantial investment to support Mr Huckfield... and going to design a new range of motorcycles for him.’ CB asked Mr Huckfield about this, but he does not recall any such proposal. Letters show Hopwood was still chasing termination payments in March 1974.