DONG HAI 750

Looks like a familiar twin, but this is a Dong Hai 750 – the Chinesebuilt parallel motor with more than a little British influence

Words MICK DUCKWORTH Photography GREG MOSS

There are loads of Chinese-made motorcycles on our roads today, but for anyone with an eye for a classic, not much of interest. Unless you come across Peter Wright and his 1968 750cc Dong Hai on the lanes of rural Norfolk. Not interested in mainstream bikes – and having always enjoyed the challenge of making Eastern Bloc machines reliable – Peter took on a mammoth job when he swapped a Soviet 650cc Dnepr MT11 flat twin for this parallel twin from even further East with a fellow member of the Cossack OC.

“I got two and a half bikes partly dismantled and in a pretty rough state, knowing that spares aren’t available,” Peter says.

According to available information, the Dong Hai was manufactured from 1968 until 1985 at a factory in Shanghai. Made for the military and primarily for sidecar use, it has an ohv 745cc (78 x 78mm) engine in a heavyweight chassis and provided a modernised replacement for the 750cc BMW-copy side-valve flat twin used by the People’s Liberation Army from the mid-1950s. (The Dong Hai didn’t fully replace the archaic design; it survived for decades, being available in the UK as the Chang Jiang CJ750 until defeated by emissions rules 10 years ago.)

An estimated 20,000 Dong Hai vertical twins are thought to have been produced, many shipped to Albania and Vietnam. A few, probably fewer than 100, were imported as the SM750 model to Germany in the 1980s and sold in civilian colours, but Peter opted for a military olive green finish.

‘I got two and a half bikes in a pretty rough state, knowing spares aren’t available’

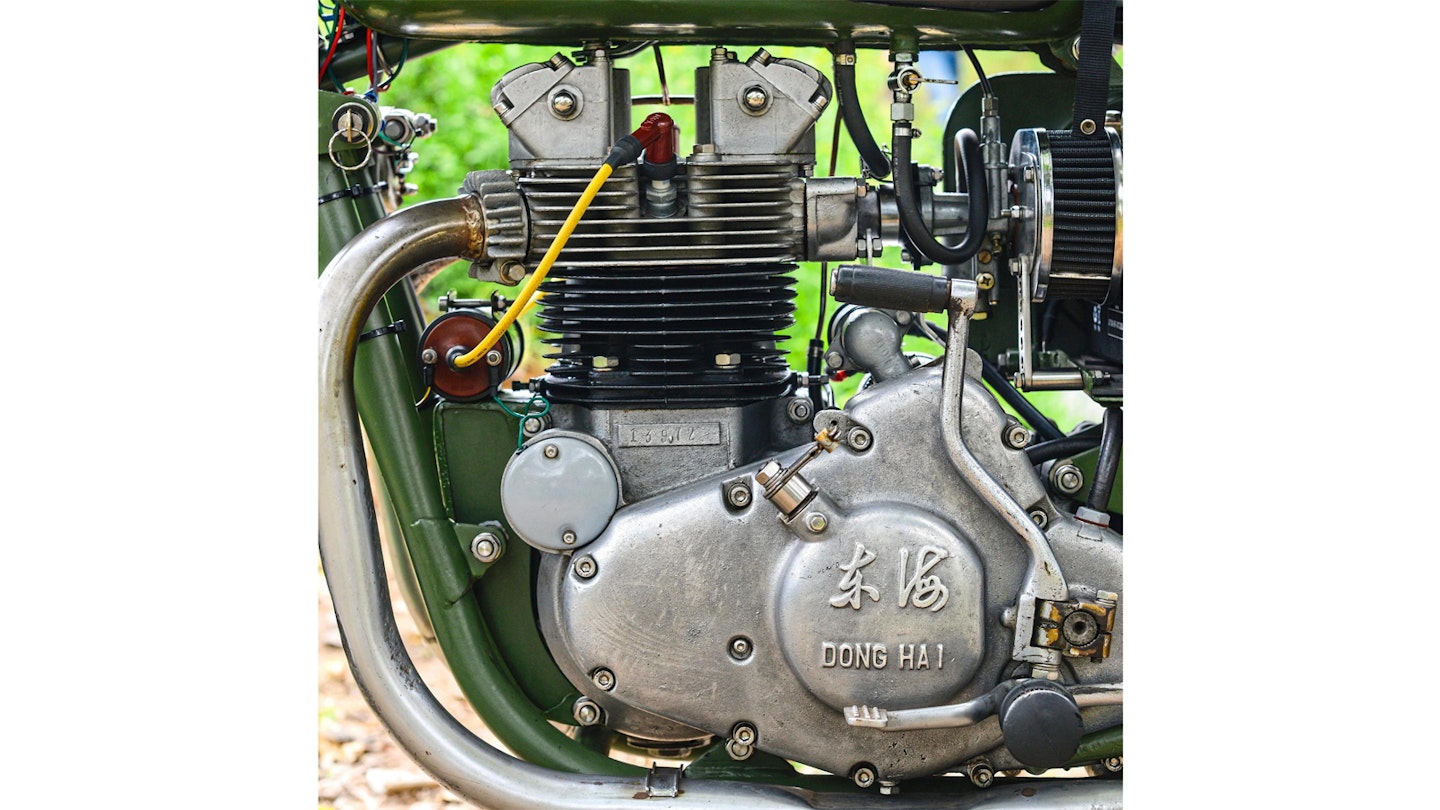

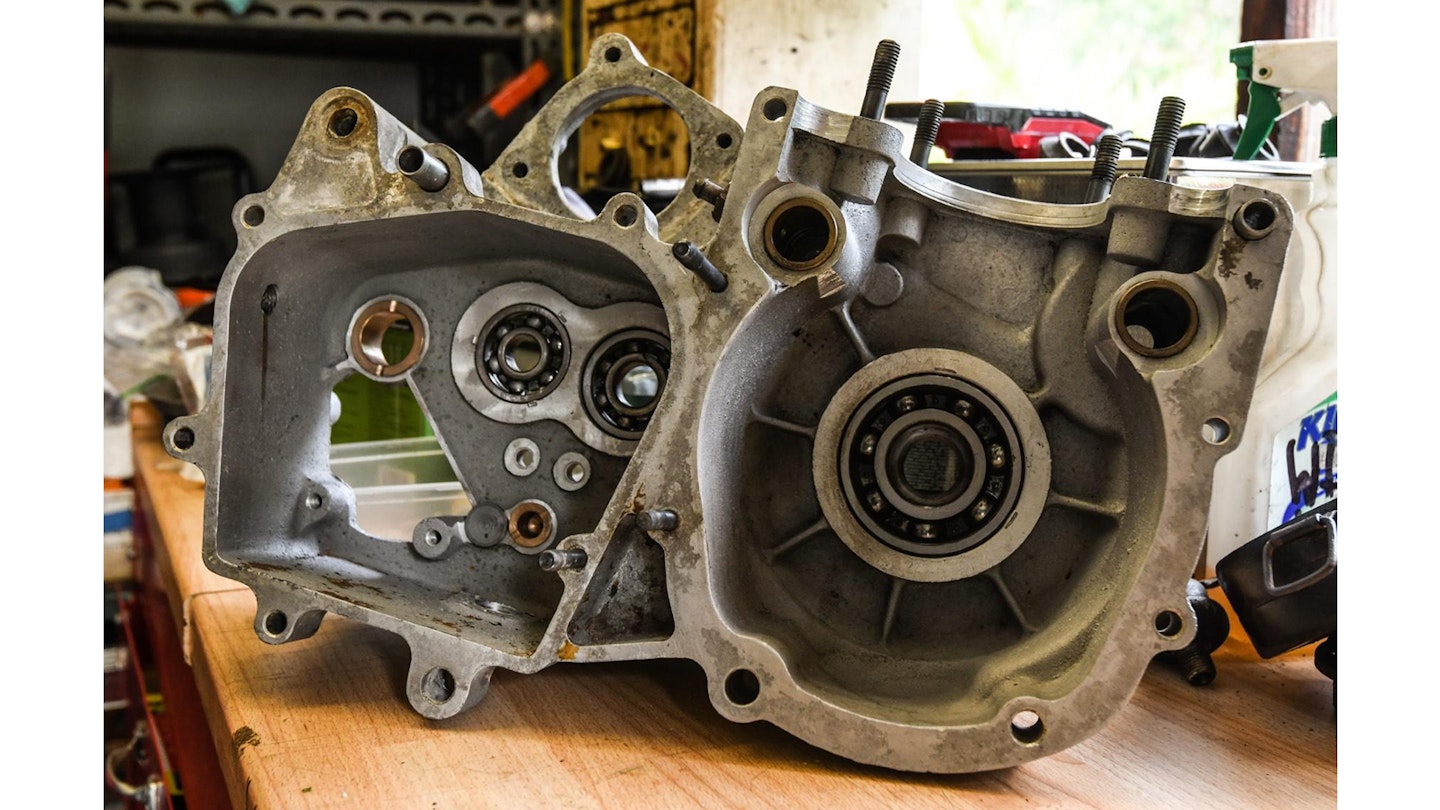

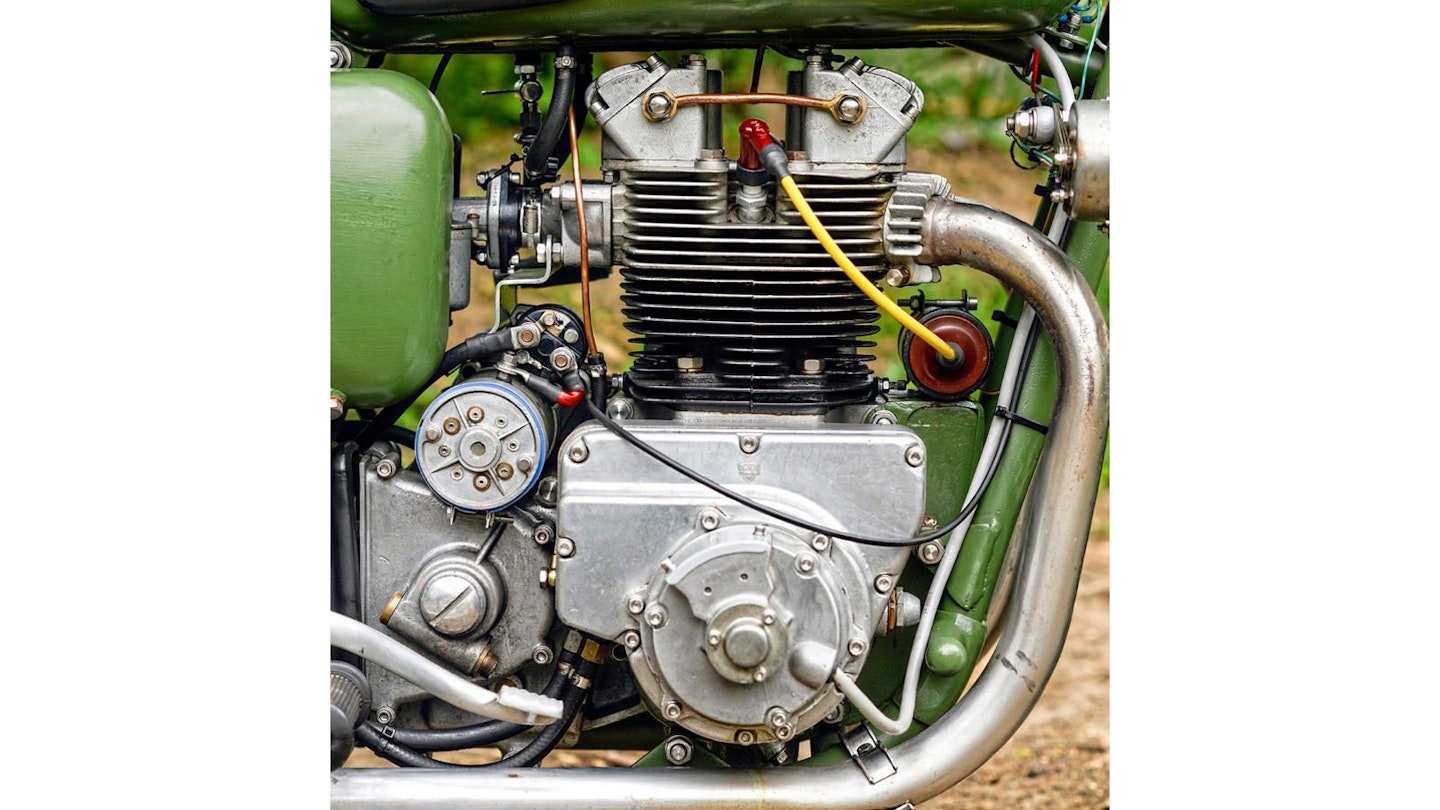

“It’s rare, but the wrong sort of rare,” he quips, acknowledging that this does not rank among the most desirable classics. As a former Triumph owner, he was struck by the upper part of the Dong Hai engine’s visual similarity with Meriden twins and triples. And as he began turning his three rough engines into one good one, he found some strong internal likenesses. As on most Meriden twins, the 360° crankshaft has a bolted-on central flywheel and carries I-section alloy connecting rods (Peter also has a spare crank with steel rods) on plain shell big ends. Like Triumph’s 1959-1968 350cc and 500cc twins, it has a plain timing-side main bearing but with shells rather than a bush. The valve gear layout is also Triumph-like with two camshafts in the upper crankcase, but they run in much more substantial phosphor-bronze bushes on the left side, where they are driven from the crankshaft by timing gears. The pushrods enclosed in tubes outside the cylinder barrel operate rockers with tappet adjusters accessed by removing cover plates. While similar in appearance to a Triumph item, the cylinder head is held down by eight bolts, where a Meriden 750 has ten.

The dry sump lubrication system’s twin-plunger oil pump, driven off the inlet camshaft, mimics that used by Ariel from 1929 and Triumph until 1985. Noting different top-end oiling systems on his engines, Peter chose a direct feed to the rocker boxes from the timing chest rather than the usual British method of a branch off the return line to the tank. He didn’t fit oil pressure and warning light switches found among the parts.

The Shanghai factory clearly studied Triumph design, not surprising since the brand was a world leader in the late 1960s and Britain had strong trading links with Shanghai prior to the 1967 Cultural Revolution. “All the alloy and castings look well-made and of good quality,” Peter says. “The only real problem I had building the engine was with the big end and main bearing shells but a local friend, Trevor Walker of TWM Engineering [01692 582850] and his computer came up trumps. He found that Renault 8 car main bearing shells would match reground journals.” Having only a carburettor with a broken body in his cache of parts, Peter substituted a similar Russian K302 type, fitting a K&N air filter.

Apart from the crankshaft, the lower part of the engine owes more to European than British tradition and certainly lacks the curvy looks of classic Triumph castings. Primary drive is by straight-cut gears and the teeth on the clutch outer drum take drive from the starter motor. The primary casing shares oil with the four-speed gearbox, which has a drum-type selector mechanism operated from a heel-and-toe pedal. A kick-starter is on the left side of the box.

Charging for the 12V battery is by an alternator mounted in the timing cover (as on a Triumph Trident), with a peg drive off the end of the crankshaft that allows it to be easily removed. The ignition points are under a cover at the leftward end of the exhaust camshaft and a double-ended coil is mounted ahead of the cylinder block.

Looking more BSA than Triumph at a glance, the duplex frame is extremely weighty with large-diameter tubing, some slightly oval-section, and has a similarly sturdy swingarm. The rear shocks, taken from Peter’s spares store, have bare springs where the original Girling lookalikes were fully shrouded. Heavily mudguarded 17in wheels are shod with wide, deeply treaded Mitas tyres. The drum brakes look weatherproof and there is a crossover rod and cable arrangement to operate the rear brake from the left pedal. A pressed steel cover encloses the final drive chain, with a flexible bellows joint where it meets the rear of the gearbox. Useful fuel range is promised by the capacious and shapely 25-litre (5.5 UK gallon) tank, which needed some holes filled before painting.

Short of a seat, Peter found one made by aftermarket brand Two Four at an autojumble and made it fit; a Cossack logo at the rear doesn’t bother him. To use original silencers, silver heat-proof paint was applied to damaged surfaces unsuitable for plating. There is a similar matt finish on the raised and swept-back handlebars, which carry a switch unit including a neat click-ring headlight dipper inboard of the left grip. Lacking a battery cover side panel, Peter used a pressing from a 175cc CZ that doesn’t look out of place. Finding the original massive rectangular rear light ugly, he replaced it with a neater Chiang Jiang unit and fitted a rear-view mirror.

The Cossack OC, of which Peter has been a member for 30 years, obtained an age-related registration from the DVLA to get him road legal. When the completed machine was first started, smoke started issuing from under the fuel tank. Concluding that it wasn’t from leaking oil, Peter decided there was a problem with the regulator/rectifier unit. A maintenance technician for a leading potato brand with no fear of electrical systems, he obtained a Yamaha XS650 unit as he knew the alternator was of a similar type to the Dong Hai’s. He mounted it under the headlamp with its heat sink in the air stream.

Once on the road, Peter has encountered some minor glitches with carburation and ignition, but he has always relished a technical challenge with unorthodox machinery.

What’s it feel like?

Hugo Wilson takes the Chinese 750 for a trundle

First impressions? It’s heavy. And it’s tall. Heaving the Dong Hai off its centrestand is a nervously precarious exercise. The ignition key is under the headstock, and without the electric starter connected it needs to be kickstarted; for me, on a bike with a left hand kick-start, that means standing alongside the bike and using my right leg. Fortunately, the low-compression engine turns over easily and fires straight away. The exhaust note has the even pulses of a 360° crankshaft and is well muffled.

Astride the bike I’m on tiptoes, but the wide bars and spacious stance make it easy to ride. The rocking heel and toe shift pedal for the four-speed gearbox is on the left, with an unusual neutral below first, heelfordown-t-oe--for-up pattern that I never get used to on this brief ride.

The low-speed manoeuvrability is good – partly helped by those wide bars and the low gearing – and while you can feel vibration at low revs it is never really intrusive and actually seems to reduce as engine revs rise.

The combination of a small carburettor and heavy flywheels ensure that speed builds slowly, and progress is sedate. The speedo wasn’t working, but it feels like not much more than 30bhp, and 50-55mph cruising. On these Norfolk lanes – and in deference to an engine that’d only done 50 miles since a rebuild – that felt fine.

Once you are up to speed, the handling is a bit vague – maybe it’s those chunky tyres, the forks are a bit clunky, and you need to use both brakes to slow the substantial mass of the machine.

Now, to get it back onto the centrestand. Er… can you give me a hand?

SPECIFICATION: 1968 DONG HAI 750

ENGINE/TRANSMISSION

-

Type air-cooled ohv 4v parallel twin

-

Capacity 745cc

-

Bore x stroke 78 x 78mm

-

Compression ratio 7:1

-

Carburation 26mm Dnepr K-302 (substitute)

-

Ignition battery and coil

-

Clutch wet, multi-plate

-

Gearbox four-speed

CHASSIS

-

Frame tubular, duplex cradle

-

Front suspension telescopic hydraulic forks

-

Rear suspension swingarm, twin shocks

-

Brakes drums front and rear

-

Wheels spoked, steel rims

-

Tyres 120/90 x 17in F&R

DIMENSIONS

-

Wheelbase 56in (1430mm)

-

Seat height 880mm (34.6in)

-

Kerb weight 569lb (258kg)

PERFORMANCE

-

Top speed 85mph (est)