RICK RIDES

The 1970s may have been the era when Japan’s two-stroke 250s caught the imagination of a generation of young Learner riders – but other options were available from closer to home

Words RICK PARKINGTON Photography GARY MARGERUM

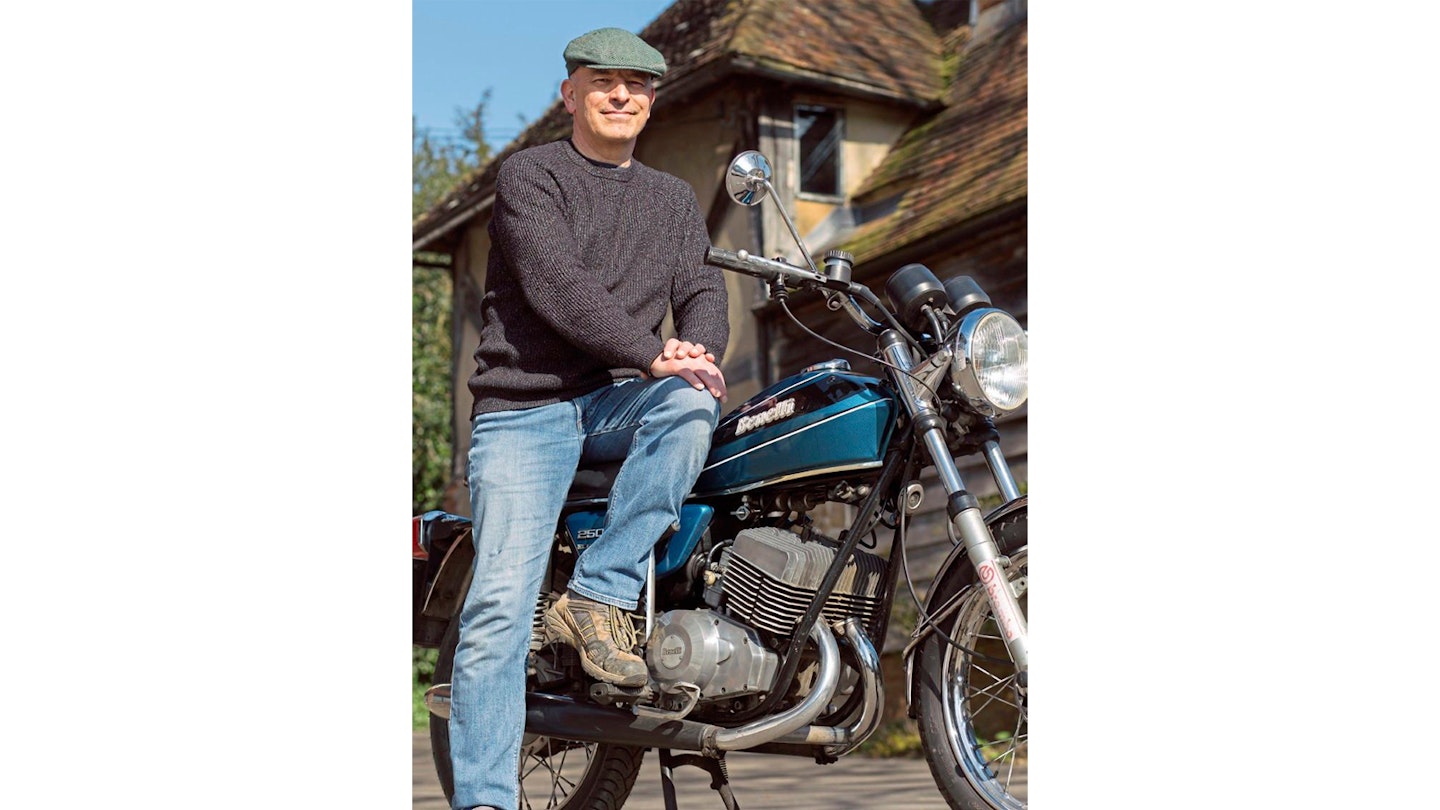

The Elettronica added a dash of Italian panache to the 250 stroker screamer pack. Did Rick click with it?

Even as a child, I didn’t like the ’70s. All the grown-up stuff about three-day weeks and Ireland’s ‘Troubles’ sounded grim and I couldn’t see how ugly, angular beige cars or avocado bathroom suites made up for it. But if there was light shining in that tunnel it came from the elevation of the 250cc two-stroke twin from the drudgery of life as an economy commuter to the glamour of L-plate mania and beyond. I’m really enjoying getting to know the Mediterranean beauty you see on these pages – but maybe that’s a bad way to put it, because this kind of bike doesn’t really take much learning.

Choke is generally needed for starting, except when very warm – it’s operated by a lever on the left carb, so it’s important not to forget to flip it off once underway. While there’s no electric start, typically for a two-stroke twin it’s very easy to kick over and sits happily burbling away until you’re ready to go. Once underway, you can just get on and enjoy it because, being Italian, it handles well. Also, as with Triumphs of the time, you get surprisingly good brakes because the scale of local industry only allowed for one product not a range of descending prices; so here you get a Brembo disc that’s much better than those on other contemporary 250s.

‘It’s an exciting bike to ride once it’s on the boil’

The Benelli is so light, manageable and compact that my initial impression is of something even smaller - like an RD200 or Suzuki X5, those handy lightweights whose Learner sales suffered from being not quite the full measure permitted by law. Pulling away and keeping the revs low, the Benelli can feel quite tame – but once you hit the powerband, its character transforms and it’s off like a banshee. Claimed power was 32bhp; I’d guess that may be fishing-talk, being a couple more than an RD250 even though its capacity (at 231cc) is significantly less. But it’s also more than 10% lighter, leading me to suspect that on the right roads the 2C could have the edge. Certainly it’s an exciting bike to ride once it’s on the boil.

One of my favourite things about two-stroke twins is that they can be silky smooth and very tractable, with the ability to purr along at modest or low speeds without getting lumpy – then, when prodded, they take off like a scalded cat and, if you get your gearchanges right, stay screeching up there to make you feel like a short-circuit star. The Benelli ticks that two-bikes-inone box very satisfactorily. I’d say the power starts to kick in around 3750rpm – with a peak figure of 7000, that’s a very useable range (although in practice, I found it paid to keep an eye on the rev counter to avoid disappointment when changing up at slower pace). At speed, the balance of weight, braking and handling really comes into its own.

Even the lever for adjusting the shocks has a touch of Italian flair

It’s quite comfortable, too. Bikes of this era, even ones intended for tear-arse teenagers, were mostly still made in the classical upright format – it was up to you if you wanted to make it look like a racer. Maybe that was because bikes still had to be multi-purpose; as well as weekend fun, you still needed to ride it to work.

Through subsequent decades, the quest for sales has led to bikes being streamlined into more defined roles; I think they’ve lost something along the way. Certainly when you look at things in classic bike terms, for those of us who want to ride rather than simply collect, that all-rounder quality combining fun and practicality is more important than engine capacity. There’s also much to recommend a bike that’s easy to wheel about and doesn’t take up too much room in the shed.

But despite its merits, I wonder how many of us, looking to relive our L-plate yesterdays, would seek out a Benelli? They were never common in the UK compared to RDs, GTs and Kawasaki triples – I don’t remember having seen one until Carlo Battain flashed past on this gleaming Mk2 during last year’s VMCC West Kent Run. You may recall that I tested Carlo’s BMW K100 in the May issue of CB, but I must admit it was his Benelli I was really looking forward to riding. He’s owned the bike for about 25 years, but it’s not his first one.

“With a proud Italian for a father, when I was looking for a bike in the mid-1990s, I was steered away from a Japanese bike and bought a Series 1 Benelli 250 2C locally. The Series 1 differs from the Series 2 in having a twin-side drum brake – which, surprisingly, I found worked better than this single disc. For a time, I had both bikes on the road at once – the difference in the brakes was quite noticeable, but apart from that this one was a much better bike. My Series 1 had clearly been hammered in its lifetime – it was slower than this one, so I ended up selling my first one.

Owner Carlo Battain’s Italian dad bought the bike in Florence

“Ironically, this one was the ‘donor bike’! My dad found it at a big market in Florence in 2000; it was on offer for about £200, so he bought it as spares for my existing 2C. But when it arrived here, despite dad saying it had been scrapped, I couldn’t believe the condition – it was far better than mine and only had about 10,000km on the clock! I think they had something in Italy at that time where, if you weren’t using a vehicle but didn’t want to pay tax or insurance, you could declare it ‘scrapped’. The only problem with that was it meant I didn’t get any documents with it, which complicated re-registration over here a bit.”

I’d assumed that Carlo had restored the, bike but in fact it’s still mostly original – even the much-maligned Italian electrics. “Yes, apart from a good clean up, all the bike really needed was new tyres and a set of fork seals. I also fitted a new seat cover, but the paint and chrome is mostly as it left the factory. Mechanically, I’ve had no problems and the electrics all work perfectly “Benelli fitted electronic ignition when even the Japanese were still fitting contact breakers and I’ve never had to touch it. Even these cheap and nasty handlebar switches work perfectly – although I think that’s mainly down to the low mileage. They were in a bit of a state on my original bike and most of these you see now have been converted to Japanese switchgear.

Powerband stetches from just below 4000 to 7000rpm – relatively user-friendly compared to other screamer 250s

“It’s a great bike for VMCC runs round the lanes – even though it can be a spiteful little bugger at times, spinning out the back wheel on damp roads and pulling accidental wheelies!”

One problem I associate with Italian bikes is spares supply, but again Carlo surprised me. “Admittedly, I’ve managed to collect up a few useful bits, including a spare engine, and if it came to it I still have family in Italy, but really the internet has made a massive difference.

Anything I’ve needed has come from Benelli-Bauer in Germany; in fact, I ordered something from them recently for the first time in a few years and it was just: ‘Oh hi, Carlo. Yep, I’ve got that...’ really great service.”

Two-fifties are a funny thing; if you passed your test on one, it’s hard not to see them as just a stepping stone – a sort of curfew imposed by a government mistrustful of our natural riding skill (aka youthful over-confidence). That sense of insult created a widespread mindset that a 250 isn’t really a ‘proper bike’. I think that’s a mistake – one that was later challenged by the RD250LC so successfully that its impressive top speed reputedly led to further learner restriction down to 125cc.

But on top of that, not everyone likes two-strokes, either due to simple prejudice or some past trauma arising from whiskered plugs or blown crank seals. If so, I’d say you need to think past that. About the only drawback I can see with the Benelli is that it’s premix – you need to mix the petrol and oil rather than having an injection system – but once you get used to that it’s no problem, especially if you’re not using it daily.

What you gain is a simplicity of design that requires minimal servicing and maintenance and gives a huge amount of fun riding in return – especially if you can find one as attractive and unusual as a Benelli.

Stylish Benelli is 10% lighter than its tearaway stroker rival, the RD250

SPECIFICATION: BENELLI 2C 250

ENGINE/TRANSMISSION

-

Type 180° parallel-twin two-stroke, air-cooled

-

Dimensions 56 x 47mm

-

Capacity 231.4cc

-

Power 32bhp at 7000rpm

-

Compression ratio 10.3:1

-

Carburation Twin Dell’Orto VHB25

-

Clutch Wet multiplate, driven by helical primary gears

-

Gearbox Five-speed

CHASSIS

-

Frame Tubular steel cradle

-

Front suspension Telescopic forks with hydraulic damping

-

Rear suspension Swingarm with adjustable hydraulic shock aborbers

-

Brakes Front: 260mm hydraulic disc. Rear: 58mm single-leading-shoe drum

-

Wheels Spoked

-

Tyres Front: 3.00 x 18. Rear: 3.25 x 18

DIMENSIONS

-

Wheelbase 1310mm (51.5in)

-

Weight 132kg (291lb)

PERFORMANCE

-

Top speed 90mph

Benelli’s history book

Confusingly, the ‘2C’ model code can refer to the 125 or 250 model. The 125cc 2C was also a two-stroke twin with a bore and stroke of 42.5 x 44mm, producing a claimed 18bhp at 8100rpm. Both models were first seen in 1972, with iron cylinder barrels and drum brakes. Both models had electronic ignition (hence the ‘Elettronica’ emblem on the side panel) from 1974, acquiring a disc front brake and ‘Series 2’ status in 1975 and remaining in production until 1986.

Benelli is unusual among motorcycle makers is having a female founder. Widowed Signora Teresa Boni Benelli used her late husband’s inheritance to set up her six sons in business at Pesaro on Italy’s Adriatic coast in 1911. They produced their first motorcycle in 1919, graduating to building their own engines the following year. For the next two decades, Benelli progressed into advanced single and double overhead cam designs driven by a trademark train of gears, culminating in a Lightweight (250cc) class win at the 1939 TT, ridden by UK rider Ted Mellors.

Like other industries in former Axis countries, Benelli took some time to recover from World War II. A family dispute saw gifted company designer Giuseppe Benelli leave to found his own company, Moto B Pesaro (later to become Motobi). After starting out refurbishing former military machines for civilian use, the main Benelli company began its regrowth with an economy 98cc model. By the late 1960s, they were producing an impressive 650cc parallel twin to rival British models – but the rising success of Japan’s motorcycle industry hit Benelli both at home and, more dangerously, in their export markets.

The 1972 takeover by Argentinian racing driver and entrepreneur Alejandro de Tomaso saw the introduction of more competitively modern models like the 2C right up to the Honda-copy four and six-cylinder four-strokes. An element of ‘badge-engineering’ with other brands from his portfolio was added too, so the 2C was also supplied as the very similar Moto Guzzi 250TS (below) as well as a near-identical 2C Elettronica from sister company Motobi.

In following years, Benelli went through a succession of owners. A high point was the 900cc Tornado Tre of the 2000s, allegedly inspired by the success of Hinckley Triumphs. Since 2005, the name has been owned by Chinese industrial giant Qianjiang who produce a range of models designed in Italy.