INTERVIEW

The three-time British Superbike champ tells us doing the TT once was enough and reveals the ideal honeymoon location

Words: John Westlake Photography: Reynolds archive, Bauer archive, John Westlake

Professional racers usually play down the sheer terror they had to overcome to compete at the highest level. Or they blank it out. Or perhaps just don’t like talking about it. But John Reynolds has no such reservations, and actually used the memories to help him retire in peace.

“I’ll always remember qualifying at Brands Hatch,” he says. “To get a fast lap, you had to nail Paddock Hill bend – to do that your braking had to be so late, you genuinely thought you were going to have a massive crash. You had to really scare yourself and I eventually realised that was a very weird way to make a living.”

We’re sitting in John’s back garden and have somehow started at the end of his stellar 34-year racing career, talking about the final season when a huge crash changed his entire mindset. Until then, John was the embodiment of determination; forcing bikes, rivals and his own fears into submission by sheer will. And it worked – he won his first British motocross championship aged 12, took three British Superbike titles, got eight top ten finishes in 500GPs on a privateer bike and won a World Superbike race, again on a privateer bike.

“My determination has always been there,” he says, sipping his tea. “Racing was never a hobby for me – I was always totally focused on trying to win. It’s funny, because I could take defeat in all the other sports I played when I was younger, but not with racing. Then I had to win. The other riders were never my mates when I was racing, because I didn’t want anyone getting inside my head. It was my job, I had no safety net and I had to succeed.”

This burning determination must partly spring from John’s early racing career, when he had to battle just to get to the start line, never mind win. Though his dad was a devoted race fan and spannered for John in his early days, money was tight and it was up to John to provide the motivation. “I did a lot of motocross as a kid – I started aged eight and was British champion by the time I was 12 – but eventually I got disillusioned with it. It was expensive and I wasn’t going anywhere.”

Hang on, didn’t you come third in the European championships, I splutter. “Yeah I did, but I was never going to make a living out of motocross – I was never good enough for GPs and I didn’t have a plan, so I packed it in when I was 18.”

But bikes were still in the foreground. John had bought a Suzuki AP50 at 16, passed his test on a GP100 and went straight out on a Honda CB900 that he’d bought in readiness for the big day. “That was a dream come true, but really I was desperate to go road racing. I just couldn’t afford it – I was a signwriter earning £200 a week and that wasn’t enough.”

Then he and his dad went to a vintage race meeting and John had an idea. His dad had a 1934 Velocette MOV 250 in the garage... “I said to dad: ‘Why don’t we do up the Velo and go vintage racing?’ He was keen, but all hell broke loose because my mother was set against road racing. She’d seen so many top riders die. It was a serious bust-up – she actually left home in protest. But when that didn’t work she came back, and dad and I prepared the bike over the winter of 1986.

“By the time we’d finished with it, it looked great, but it was slow and struggled to get up the hills at Cadwell. I absolutely loved the racing, though. This was it. We raced the Velo three times and I won a few races and got my knee down, then it blew up at Snetterton. But dad saw I had potential and he loaned me the money to buy an RD350LC. I did quite a bit of winning on that.” So much, in fact, that a sponsor loaned him a TZ350 to see what he could do on that. The answer? Win the British ACU 350 Championship.

In 1988 Ray Swann and Roger Hurst were riding GPX600s for Team Green Kawasaki, and when Roger got injured, a well-connected friend from John’s motocross days suggested he got a try-out. “I was petrified, because I knew it was an opportunity that I couldn’t waste. But I finished sixth and a week later Colin [Wright, Kawasaki team boss] said he had a 600 TT bike that was sitting around doing nothing and asked if I wanted to race it.

“Obviously I did, and a few races later at Snetterton, Roger and Ray were battling for the lead and I was closing on them. I overtook Roger, then Ray and was leading into the last corner. But Ray got me back, while Roger crashed trying. So I finished second and Roger came third, crossing the finish line sliding on his arse.”

Colin Wright’s father, Alec – legendary Kawasaki race boss and inventor of Team Green – saw the whole scenario play out, and was obviously perturbed that a whippersnapper had very nearly mucked up Kawasaki’s title challenge. “Alec took me behind the garage for ‘a bit of a chat’. I thought I was in for it. He said: ‘That wasn’t in the plan was it? But f**k it, what a good ride.’ In other words: don’t mess about with the factory riders again, but well done anyway. Roger and Ray didn’t say anything, though – they really didn’t like me.”

Not that John cared. The following year – 1989 – Kawasaki signed him up as a full-time rider and he raced everything from the new KR-1 250cc two-stroke to a ZXR750 H1 in British Superbikes and a ZZ-R600 in the Isle of Man. Ian McConnachie beat him to the 250 title, but he had more luck with the ZXR750. “Roger and Ray could never get it to win, but I managed it at Oulton Park in the wet, beating the Nortons. I think that convinced Kawasaki they could get me on a bigger bike.

“The TT ride came about because Roger and Ray were both good over there and I’d always wanted a go. Shelley [his then girlfriend, now wife] and I went to the Island in March and I did loads of laps in a car. I pretty much knew where I was going… in a car. The first practice I was on a KR-1 and by the time I got out of Union Mills I was totally lost. It was properly scary.

“Then Hizzy came past me at Barregarrow like I was standing still. His bike bottomed out and he wobbled off in a cloud of fairing dust. I thought there and then that if that’s what you need to do to win a TT, you can stuff it. I wasn’t prepared to do that.”

John was newcomer of the year and did a 110mph lap at that TT, so he wasn’t hanging around. He’s clearly a gent prone to massive understatement these days.

He’s also no idiot. “There were five riders killed that year – Phil Mellor and Steve Henshaw among them. It was tough seeing all those vans left there at the end. That brought it home. You don’t get a second chance at the TT and I knew I was prone to making mistakes.” John never went back.

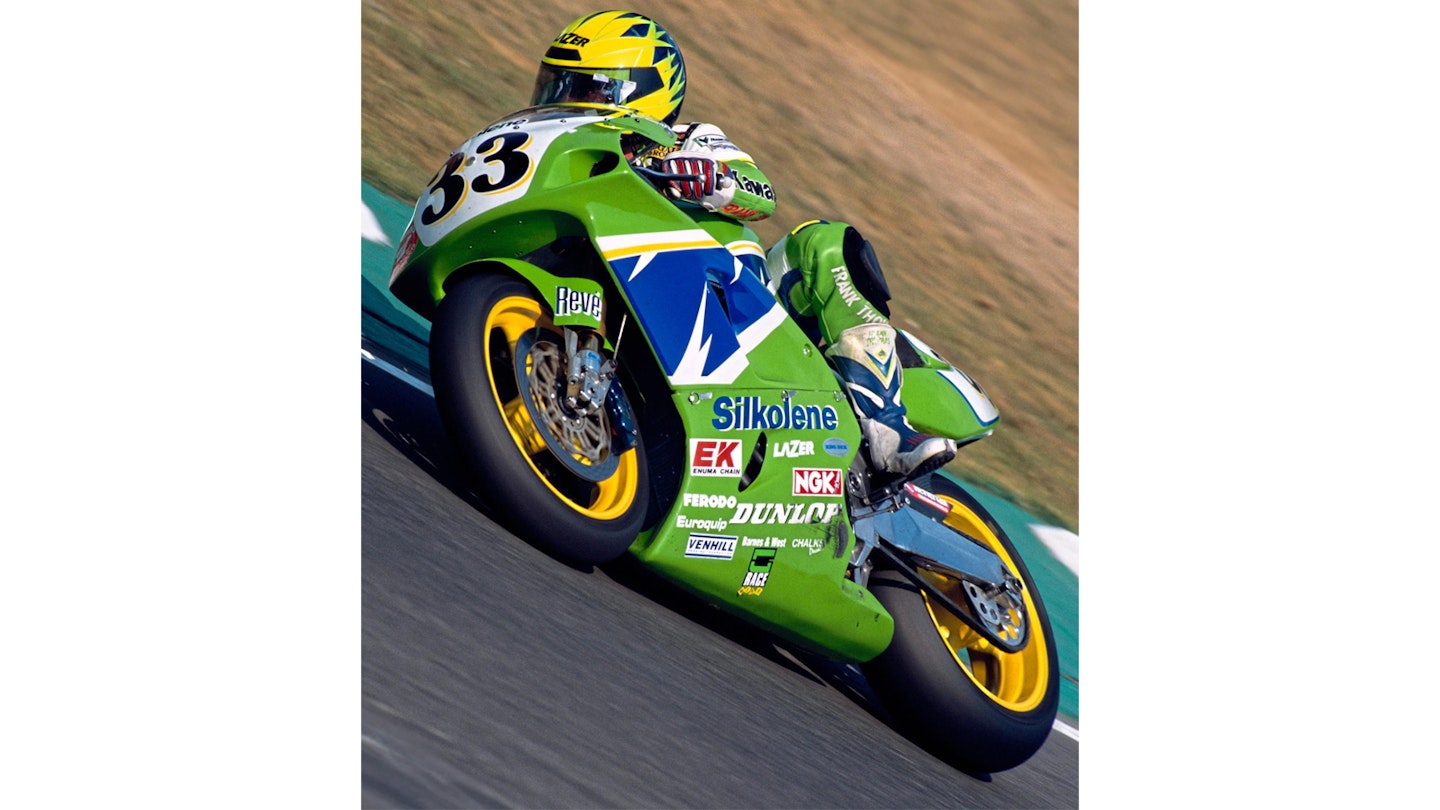

After a year spent winning the British 600 championship on the new ZZ-R600 – “a massive fast thing, we had to remove almost all the suspension movement, so it was like riding a brick” – Kawasaki finally decided to give John a permanent Superbike ride on the latest ZXR750. “It was great, but we were running Pirelli tyres. I’d do six or seven laps and look like I could win, then the tyres would drop off a cliff and I’d end up going back to sixth or seventh. Colin Wright thought it was my fitness, and at Oulton it came to a head. I said: ‘Put Dunlops on it and see what happens then’.

‘We raced my dad’s Velo MOV three times... I won a few races and got my knee down’

“But he called my bluff and fitted Dunlops with Pirelli labels stuck on. Luckily I qualified on pole, won the first race and kept on winning from then on, ending up third in the championship.”

In 1992 the team officially switched to Dunlop, so John was one of the favourites. It wouldn’t be easy, though, as the field was packed with talent: Carl Fogarty, Rob McElnea, James Whitham, Jeremy McWilliams and David Jefferies, to name a few. Still, John beat the lot and won his first BSB title. “That was fantastic, but towards the end of the season Colin [Wright, the team manager] said they weren’t sure the team would continue next year and that I should start looking for another job. That was a blow.”

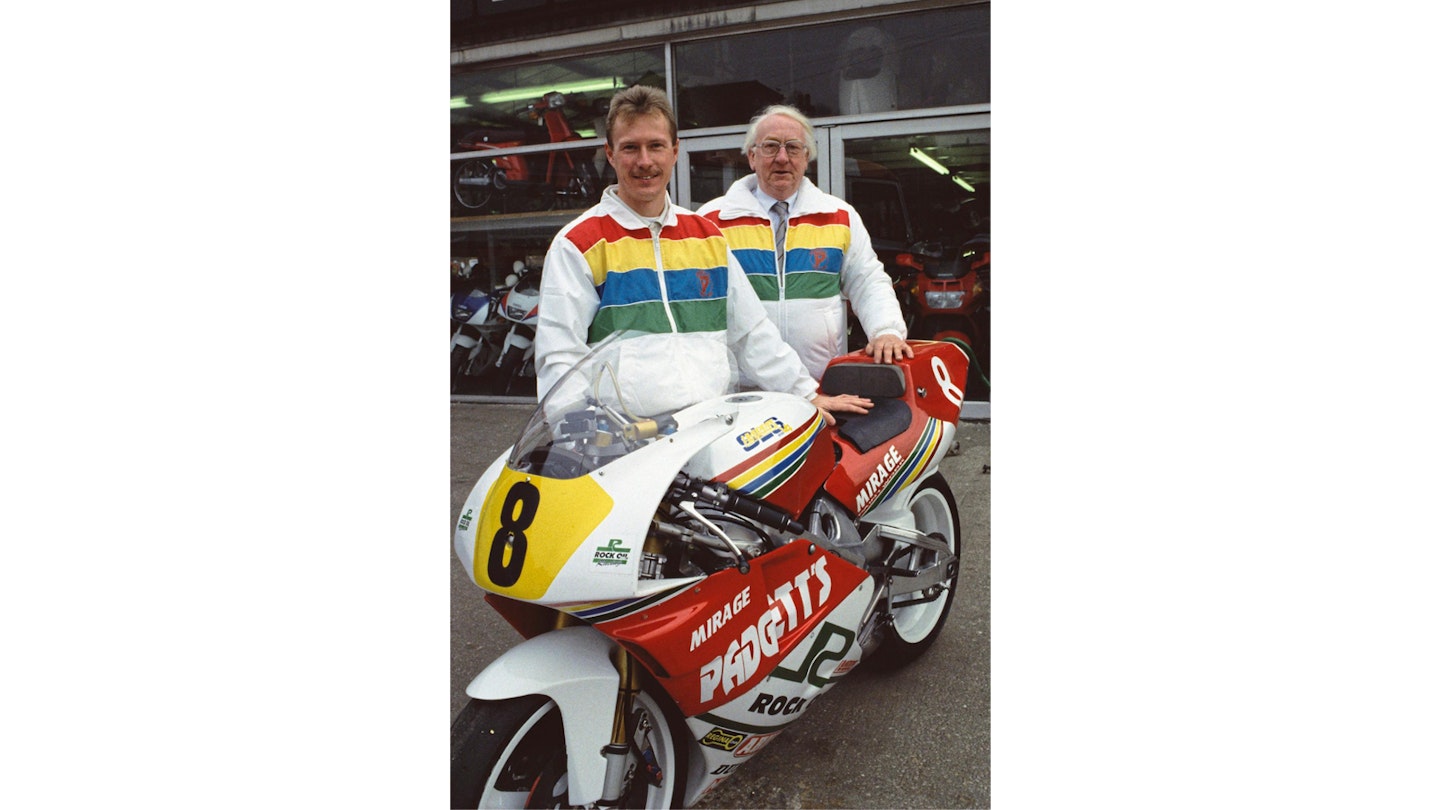

Fortunately, ace dealer and team boss Clive Padgett came up with the solution, offering John a ride in 500cc GPs on a Harris Yamaha. John explains how exciting it was to be heading off to Australia for his first ever 500GP, when his wife Shelley pops out with more tea and a pertinent fact: “That first round at Eastern Creek was our honeymoon – look, there’s a photo of me cleaning a radiator.” And sure enough, among the pile of snaps on the table, there it is.

“You really took your new wife to a GP for your honeymoon and made her work in the pits?” I ask John, marvelling at his radical approach to marital bliss. “Well, I’d just got the ride, so it was the obvious thing to do. Shelley loved it,” he says, grinning.

“It’s true,” says Shelley as she wanders off.

“But I crashed that Harris a lot. A hell of a lot. I kept losing the front. Looking back, having ridden bikes with proper factory suspension since then, there was a problem with the forks. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the experience to work that out.”

John doggedly tried to ride around the problem, but he couldn’t. He got eight top 10 finishes, but was plagued by the Harris front end. “They were hard times. We did another season in 1994, but it didn’t get much better and I knew that was the end of GPs for me.”

Plenty of racers in this position would have struggled. But his mate Ben Atkins decided to start a WSB team for him. “It was really exciting, because back then WSB was massive – all the factories were involved and there was huge interest. We put the bike on the podium a couple of times, but Ben had heard a rumour that Suzuki were setting up a factory team and he suggested they take me on. That’s how I got the factory Suzuki ride.”

John’s team-mate was Kirk McCarthy, the Aussie superbike champion and infamous hell-raiser. “He missed the first test, because he’d been out celebrating winning the Australian Superbike championship and ended up in jail after getting caught drink driving. He made it to the next test a few days early with the rest of us and we decided we’d all go out for a meal and a few beers. After that, some lads – Trevor Nation was there – said they were going to hit the town, but I’d had enough and they dropped me off at the hotel.

“The next morning I came down for breakfast and noticed Kirk wasn’t there. Turns out he’d had a skinful and was driving when Trevor yanked the handbrake to do a handbrake turn right in front of the local cop. Kirk ended up in the slammer for two days. I remember the crew chief getting nervous because he had to phone up Steve Harris [the team boss] to tell him Kirk was in prison again.”

Though John was the top Suzuki rider in WSB in 1996, he got wind of rumours that he was being replaced by Frankie Chili and started making plans with Ben Atkins to return to BSB on a Ducati. The pair once again made an excellent team, with John taking his second BSB title in 2001. By then John was 37, but showed no sign of slowing down. He rarely crashed and could be relied upon to pick up podiums – over his entire BSB career, he finished on the podium in over half the races he started.

We’ve finished our sarnies and it’s time I left John in peace, but we haven’t touched on his final BSB title win or that career-ending crash. “The game-changer was the GSX-R1000 K3,” he says. “It was smaller, sharper, lighter and faster – and at the first race of 2003 I was quickest in practice. But I highsided and broke my collarbone on the Superpole lap, so that was the championship gone to Shane Byrne. But the following year I won the championship.”

So, after starting at the end, we’ve come full circle to that crash at Brands Hatch in 2005. “I was bedding in some new gloves in free practice and on the third lap everything was great – the bike felt perfect and I was quick. I came out of Druids on the gas, and shut off to hit the brakes for Graham Hill bend. Except I hadn’t shut the throttle off properly, because the gloves had bunched up and I went onto the grass.” John slammed into the barrier, lying motionless on the grass.

“I remember hearing Toby Branfoot [the circuit doctor] say he was going to do something to help me breathe. He stabbed me and put a tube into my lung because it was punctured; once he’d inflated it again, I was fine.” Fine? I seem to remember he was horribly injured. “Well, I’d broken my neck, back, collarbone and four ribs and spent seven weeks in hospital.

“That was it. I decided I was finished with racing. And it was a lovely feeling – all the weight came off my shoulders, all the stress went away. A switch had flipped and I turned into a different person.” One who didn’t want to scare himself half to death for a living? “Exactly. I’d had a long career. I gave it my everything and I had nothing left. I’ve got no regrets.”